Museum to serve South Frontenac has roots in Verona area.

One of the conditions that were set out three years ago by South Frontenac Council when they agreed to support turning the former Hartington Schoolhouse, which is township property, over to the Portland District and Area Historical Society for a museum, was that the museum would be called the Township of South Frontenac Museum and will serve the entire township.

The Society was happy to agree. One issue that they are facing as they prepare the museum for its grand opening in August, however, is that although it is a beautiful building that has been well maintained and upgraded, it is a one-room schoolhouse and is not large. The amount of material that has been gathered over the 14 years the society has been up and running, when added to items that are stored in garages and attics throughout the township, far outstrips the capacity of the new museum.

A lot of materials are stored in members’ homes, and it will likely stay that way for quite a while.

This embarrassment of riches means that the museum has the pick of the crop as far as what is on display, and will be able to change its display easily over time to feature different aspects of the past in the region.

Barb Stewart and Irene Bauder met with me at the museum last week, as it is about to undergo some minor renovations in May. These will include the building of a new stoop and a fully accessible entrance, as well as the installation of new windows.

The windows are being produced by heritage window expert David White, who happens to live in the township, and Barb Stewart said they “are perfect, exactly right”. The stoop, accessible ramp and door are being put in by township staff as part of the contribution the township is making to the project. The township also helped in securing a $50,000 grant for the project.

“We hope to be back in the building by the end of June,” said Stewart, “which will give us six weeks to set up for the grand opening on the 15th of August.”

By opening in mid-August, the museum will be up and running when the three-day Frontenac County 150th Anniversary celebration takes place August 28-30.

The Portland District Historical Society had its roots in a series of meetings that took place in 2001

“Its charter members were Bill Asselstine, Inie Platenius, Enid Bailey and Jim Reynolds. They would meet over at a cottage on Rock Lake once or twice a month, and they would yak and talk about developing a historical society, and eventually having a building,” said Barb Stewart.

In 2002 the Verona Heritage Society was founded, but soon afterwards, concerned that people were saying it was all about Verona, the name was changed to the Portland and District Heritage Society, and it has had that focus ever since.

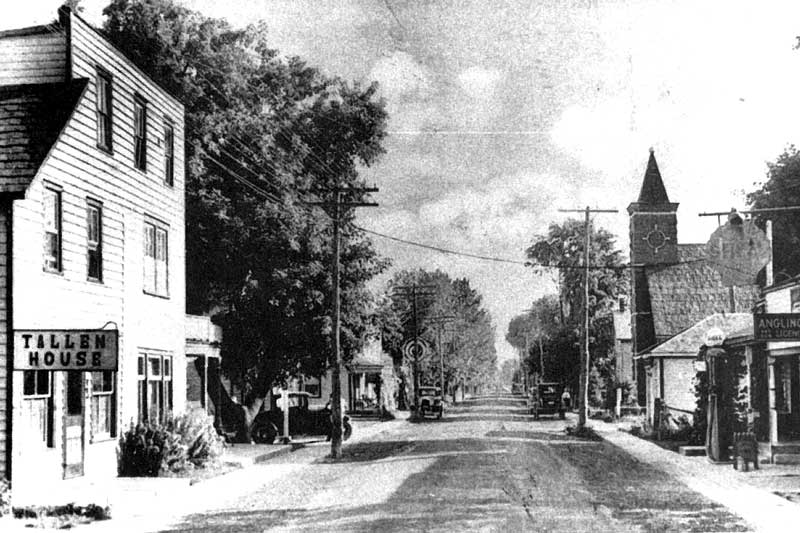

The focus on Verona at the start is a recognition of the central role that Verona held as a commercial hub in the post-war period.

The focus on Verona at the start is a recognition of the central role that Verona held as a commercial hub in the post-war period.

Photo left: Verona in the 1930's.

Barb Stewart moved to Verona from the farm that her family ran on Road 38 at Cole Lake in 1949. Irene Bauder did not arrive in Verona until 1960, but they both remember how many businesses thrived in the village in those days.

Barb Stewart's father built a cold storage plant in the location where Asselstine's Hardware store is now located. The storage plant included a butcher shop and lockers where clients could store their meat and other frozen food.

“In 1949, fridges had very small freezers in them, and even later when the freezers went across the whole top there wasn't much room. So we had quite an operation there. My mother did all the butchering, and she had all the saws and hamburger machine and everything. She charged 3 cents a pound for butchering and the lockers were between $10 and $12 a year, which people think is laughable now, but money wasn't as good then. I made 50 cents an hour working at Walker's store,” Stewart said.

“There were all kinds of businesses in Verona at one time,” said Irene Bauder.

Where Topper's Convenience Store and service station is located, there was a motel. Eventually they built another big building, which was partly an extension of the motel and was also a health food store. However before all that there was Snider's Service Centre and a restaurant.

The Heritage Society has compiled a list of businesses that were up and running in 1951. It includes two car dealerships: Revell Ford, which is still a thriving enterprise, and Verona Motors, which was a GM dealership owned by Jack Simonnett, who later moved it to Parham and then Sharbot Lake. There was a laundromat, E.L Amey's auction house and hall, Genge Insurance, a pool hall, a number of stores, the Bank of Montreal, which has been located in a number of locations and is still in Verona, and there were several restaurants, two barber shops, and more.

“When I moved here there was any kind of trade and service you could imagine,” said Irene Bauder.

Verona was the retail centre serving a swath of territory spread out in all directions, from Westport to the east, Harrowsmith to the south, Sharbot Lake to the north, and Tamworth to the west.

Although compared to many of its smaller neighbours Verona has remained as a retail destination, with hardware, grocery and gift stores, government services and banking as well as restaurants, a pharmacy and the ever-successful Revell Ford Motors, the retail sector is a shadow of what it was in the 1950s and early 1960s.

One of the reasons that has been pointed to in the past is the fact that Verona, and Portland, remained dry right up until amalgamation in 1998, with a liquor/beer store opening up only when the Foodland store moved to its new location a few years ago.

“People did start heading to Sydenham and Sharbot Lake and Westport for alcohol and that hurt,” said Barb Stewart.

Other factors included the closing of the K&P Railroad and the fact that people tend to travel more readily for shopping than they did 50 years ago.

“We are less than 20 minutes from Princess Street and Gardiners Road as we sit here,” said Irene Bauder, “and people work in Kingston and shop in Kingston.”

The former schoolhouse, which is in the final stages of conversion to a museum, started life in 1903. It did not have electricity installed until 1947, and it closed in 1954. It was used for meetings sporadically after it was closed as a school. In 1967 the Frontenac County Library opened a branch in the building. The branch moved to the new Princess Anne building just across the parking lot in 1982. Community Caring (now Community Caring South Frontenac) then opened up a thrift store in the schoolhouse. When Community Caring moved to the Princess Anne building as well in 2012, the township agreed to dedicate it for use as a museum.

As the opening date of the museum approaches, there are reams of documents and numerous artefacts to be organized. The plan is to have several small exhibit spaces in the museum, each devoted to different themes, from agriculture to military history, to education, and beyond.

Jim Reynolds, one of the original members of the group that met at the cottage on Rock Lake back in 2001, is one of two people who will be preparing a layout plan for the museum once the construction work is done.

In the interim, the Township of South Frontenac Museum will have a display at the township offices in Sydenham as part of the Open Doors Frontenac County event on June 13.

Barb Sproule: 35 years in teaching; 20 years in politics

Barb Sproule is not a lifelong resident of the Ompah area, but she has learned to fit in over the years.

She spent her first seven years in South Porcupine, near Timmins, but when her father was injured while working in a gold mine, the family moved back home to Ompah, where both her parents were from.

“It was a big change for me, moving from South Porcupine where there was an arena, stores and a big school, back to Ompah with its one-room school house. But I didn't mind, as far as I can remember. There was always lots to do, and that has never changed for me.”

Her dad was not completely done with mining, however. Years later he was involved in a plan to re-open a gold mine near Ardoch that had been closed since early in the 20th Century.

In the late 60s a couple of men approached him to help them open the Borst mine, and her father, who was a Shanks, took Barb and her husband to see the mine. They climbed down a 75 foot shaft, which Barb said “was not exactly something I enjoyed.”

The two men died in a winter storm in Northern Ontario and that was the end of the last gasp of the gold mine industry in North Frontenac.

When Sproule was young she also worked with her grandparents, the Dunhams, who owned the hotel in Ompah. There were three saw mills in Ompah in those days and she recalls that between summer traffic and logging, the hotel was “more or less fully occupied summer and winter".

After finishing grade 8 at Ompah, she went to the new high school in Sharbot Lake, using the bus service that was also new, and graduated in 1954. By the fall of that same year she was teaching at Canonto School, at age 16.

“I was too young to go to teachers' college, but they couldn't find a teacher for the Canonto school and they knew I was intending to become a teacher so they offered me the job and I accepted it.”

Some of the 16 students were close to her age and one was the same age and bigger than her, so her solution to facing up to them was to not let on she was so young. That became harder to do when the Toronto Star send a photographer to Canonto to take her picture because she was the youngest teacher in Ontario that year.

At that time teachers' college consisted of two summer courses and a full year course. Sproule went to Toronto for part of her education and Ottawa for the rest, and had her teaching certificate by 1956. She later transferred to Ompah and when Clarendon Central opened in the mid-1960s she taught there, and remained until she retired from teaching in 1989.

Clarendon Central was a three-room school, and at the start there were 150 students at the school. Barb taught grades 3-5 and had 50 kids in her class.

“It worked out fine. The older children taught the younger ones and everybody helped out,” she said.

The biggest decline in the local economy took place in the 1980s.

“The logging was in decline and people began going to Perth for work and the local businesses began to close. That was when all that really started to happen. It's too bad really that we've lost so much, and we really miss the restaurant; losing it has hurt everyone,” she said.

Political career 1978-1997

It might not be the case that all politics in what is now ward 3 of North Frontenac and used to be Palmerson/Canonto Township revolve around the fire department, but it doesn't miss being so by much. So it is not surprising that Barb Sproule entered politics in the 1978 election in order to establish a fire department, which is something that the reeve of the day was reluctant to do.

“We had a committee that had gotten together and was working on setting up a fire department and the council of the time would not support us in any way. So, we got some money and some property donated, and we bought a tanker truck and put a motor on it, which they got from emergency services out of Kingston. The reeve went and took the motor out of the truck. So I went to the reeve and said, 'Are you going to support it or not support it?' They didn't give it any support, even support in principle, so I told the reeve I was going to run, and I did and I won.”

When asked who the reeve of the time was, she said “Well, I don't want to embarrass relatives” - an answer that doesn't really narrow down who it was, given the close knit nature of the community.

Sproule served as reeve for five of the next terms, losing in one of the elections and winning the others, and was the reeve during the amalgamation process in the late 1990s.

Like a number of the Frontenac County reeves at the time of amalgamation, she retired from politics instead of running in North Frontenac, although she has continued to sit on the Committee of Adjustment to this day, and regularly gets asked if she will run whenever election time approaches.

“I enjoyed being in politics, but I like to travel nowadays, and I feel I've done my time,” she said.

During her time as reeve, the first Official Plan for Palmerston/Canonto was brought in. In 1982 she served as county warden, the second woman to hold that position in the 118 years of the County's existence. The first was Dorothy Gaylord from Arden, who served as warden in the late 1970s and was still on the council when Barb had the position.

When amalgamation was forced on the local politicians, there were a number of options on the table.

“Those of us from the north end were really wary of the idea of one township for the entire county, which was one of the options, because we felt those from the south were really dealing with a different kind of community than ours. There was also talk of one township for the seven townships north of Verona, and we didn't like that either because we were worried that more attention would be paid to the townships that became Central Frontenac because they were bigger and we thought we might not get our share. So we set up North Frontenac and I think we did the right thing.”

She recalls that the idea of eliminating the County level, which happened in 1998 and was overturned in 2004, was something that the four townships decided to do once they were established.

“They didn't realise that by doing that they would be losing out on grants, so they made the right decision to reverse it, but they wanted to run things without the county interfering; that was the thinking.”

Although she still follows politics, it is from a distance, as Barb Sproule has become somewhat of a world traveller in recent years. Her latest trip was to Australia last October, and she has made many trips over the years, with friends, on her own and once with one of her grand-daughters.

She continues to live in Ompah, in the house she shared with her late husband, and still helps out in the cottage and campground business on Palmerston Lake that she and her husband started and her retired son now manages.

Although the bright lights of South Porcupine were lost to her when she left (she did get to see the Olympic champion figure skater Barbara Ann Scott at the arena there when she was very young) there has certainly been enough going on at Ompah to keep her busy over the last 70 or so years.

Mel Good; the voice of the Parham Fair

Mel Good likes to say that he was born on Parham Fair Day, September 7, 1920, and “that was the only fair that I have missed

since then.”

Mel ended up sitting on the fair board for 50 years and for many of those years he was the MC of the fair.

“I never told any off-colour jokes,” he said, “but I did tell some corny ones, you know, like 'after you sit on them planks for a couple

of years your pants get sore'; that sort of thing.”

He remembers a time when the fair was something that people spent the entire summer waiting for, and when there wasn't a lot of money around to spend at the fair.

“One of the most important things I ever did as a director of the fair was to talk the fair board into making the fair free for children

under 12,” he recalls.

He got the idea after noticing a young girl sitting on the fence at the edge of the fair one hot sunny fair day in the 1940s.

“She had come down all the way from Sharbot Lake. I don't know how she got there, but at the end of the day I realised that she didn't have a quarter to get in. She just sat swinging on the fence all day, listening to the music. I don't think she even had anything to eat...I pushed that motion on them and they fought it a bit, but finally they went for it. The next year attendance at the fair doubled, so people said it hadn't been that bad an idea

after all.”

Before Mel's father bought a farm property near Parham in 1916 and began raising cattle and running a mixed farm, the Goods had been working as loggers, for some of the major lumber barons of the 19th century, such as HG Rathbun and John Booth.

But Mel was raised on the farm. He remembers blowing the whistle to call the men to lunch when he was five years old, and he kept a herd of Simmental cattle until about 15 years ago.

“I sold them for an average of a thousand bucks, which was pretty good because right after that the mad cow came in and they weren't worth half that. Still it was better than when I was a kid. We used to sell 10 to 12 a year for about $10 each, and those were 800 lb. animals."

One March day in 1930 when he was nine, he was gathering sap with his father when they heard a plane.

“It was a foggy day, desperately foggy, I remember. I was helping my dad make a sleigh that we used for gathering the sap. We heard a plane overhead and heard the motor shut off three times and then a big crash. We ran out there and saw the wreck. There was 22 inches of ice out on the lake and the

tail end of the plane was all you could see of the plane; it was standing straight up in the ice. I got a glimpse of the two men inside the plane but their bodies were badly mangled and they were clearly dead. Seeing that really made an impression on me, and it showed me that there are a lot of rough spots in this world. It was a sad day for sure.”

When Mel was 20 he started working in the shipyards in Kingston, and he remembers it was steady, hard work but the workers were considered crucial to the war effort.

“I went to see about enlisting, and they said I was qualified but that I should go back to the shipyard where I could do more good.”

In 1946, Mel returned to Parham to take care of his mother, keep up the family farm and to purchase the general store in Parham. With his wife Doris and her sister Jean he ran Good's store for 53 years until selling it to Hope Stinchcombe in 2009. Not only did they run the store, they also ran the post office and the train station for 25 years.

"We sold a lot of feed over the years, and a lot of everything that people needed. If there was something we didn't have, we could get it."

They also gave credit, as many stores did in those years.

“Most people were pretty good, but there were always some who took advantage,” he recalls. “One lady ran up $500 and then phoned over the next month looking to start another line of credit. But we kept good records.”

One thing that Mel remembers is the numbers and prices of products, what he sold things for and what they cost him, and most importantly, how much he made and how much work he had to do to make it. Over the years, that understanding of the value of things has stood him in good stead, and ensured his prosperity even as Parham became less and less of a center of commerce.

“When we had the train station and the truck traffic and all the farms were going strong, Parham was pretty busy, but the store kept us going all the way until the day we sold it, I can tell you that.”

He also understood the value of real estate. The farm, which is 500 acres and has a significant amount of frontage on Long Lake, is still entirely in the Good name.

“There were lots of people who sold waterfront lots for $200 in the 40s and 50s, which was a lot of money back then, but I told them they were selling off their most valuable thing for money that would be gone in a year. I still have all the value in the waterfront here.”

The other thing that he has always done, and continues to do now, is collect and preserve artifacts from the past. Whether it is the wing of that plane that went down on Long Lake in 1930, which Hope Stinchcombe found in the store three years ago when she was re-doing the floors, or a crosscut saw from the late 1890s, which he donated to Central Frontenac Township and now hangs in the township office, to records from the past and all kinds of tools from the 18th and early 19th centuries, he has collected it all.

He also has a story to tell about most of the items. He is pretty spry at 95 and is hoping to live longer than his mother did. She made it to 102.

Ravensfield Farm: Titia's Land Loving Journey

by Jonathan Davies

Titia Posthuma believes that all land deserves to be loved. Anyone who farms knows that land is classed by its current capacity to grow desirable, marketable crops, and Frontenac County, while it has a beautiful diversity of landscape, and some great agricultural ingenuity, is not known for an abundance of prime land.

More than 20 farmers from across the region, brought together by CRAFT (Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training), gathered at Ravensfield Farm on April 8 for a full day of touring fields and back country - not to bask in pristine, manicured pastures but to become more fully aware of the complex bio-systems that farms are, and consider what the farm wants to become above what we want from it.

"Observation is king," says Posthuma.

When she bought a 200-acre farm in the Maberly area in 1981, it was an overgrazed desert, a condition that would not be cured with a quick high-tech fix. It was not until 1989 that she began to earn a livelihood from the farm, growing vegetables and raising animals for meat and for fertility. Over the decades, she has paid attention to soil in ways that most farmers never consider.

For example, when she sees thistle - the "worst of the weeds" that "won't let go", instead of simply eradicating it, she first takes its presence as a sign that the soil is communicating a likely calcium deficiency - and a need for amendments, including an increase in humus.

When she sees prickly ash - an equally offensive plant - she sees a shade source and deterrent to animals that would otherwise disturb tree seeds.

And where farmers first settled the region by burning forest to clear cropland, Posthuma recognizes their immense value: namely that a soil's stable nutrients are derived not from grasses and animal manures, but from tree matter like leaves and chips, which form the basis of any healthy soil.

As the tour group stood in a grove dotted with a mix of evergreens and deciduous trees, Posthuma asked, "How many trees do you see that would have been here 30 years ago?" Apart from a few sturdy oaks, almost all were not much older than me. The forest is slowly being regrown.

While Posthuma's land has seen transformations since she began working it, she knows how quickly ecosystems can be degraded. She introduced me to the writings of Sir Albert Howard, who studied soil in the early 1900s and reported, in his book "The Soil and Health," "The foundation of industrialization has been impoverishment of the soil."

He noted that between 1914 and 1934, there was more global soil loss than in all of history prior to that time. As the soil is neglected, rains become unabsorbed and floods abound, as do wind erosion and drought.

The United Nations has declared 2015 “The International Year of Soils.” The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has cited issues such as a loss of organic matter, salination, and erosion of soils as being tied to unsustainable land management practices. These can include a variety of industrial practices, from mining to oil and gas extraction, but also agriculture.

A 2013 United Nations report, titled "Trade and Environment Review 2013: Wake up Before it's too late" recommends an increased prioritization of farming methods like those Posthuma espouses - small-scale and ecologically-focused – as a measure in helping preserve soil, and in doing so, ensure food security. In essence, the report suggests a counter-intuitive argument that organic and small-scale agriculture - often perceived as being less efficient than industrial agriculture - are crucial to feeding a growing population, in contrast to chemically intensive, biotechnology-based practices.

Meanwhile, food industry groups and government food and agriculture agencies have put forth the argument that organic agriculture is no better than what is currently the norm in Canada, and prioritizing it would lead to a great increase in land use for the same output volumes.

A recent publication, entitled "The Real Dirt on Farming" (published by Farm and Food Care Foundation) states, "there is no evidence that organically produced food is healthier or safer than food that is [conventionally grown]."

When I presented Posthuma with this quote, she noted that the merits of organic practice depend on the degree of commitment to its principles.

"It's how you're doing it that matters. There are a lot of dedicated people that are going the extra mile to work with their soils, to increase the nutritive quality of the food that is being grown on that soil, and that food has been demonstrated time again to have a seriously increased nutritional impact of a positive nature."

For consumers, or "eaters," the issue of price is often as important as nutrition and ecological viability. As “The Real Dirt on Farming” states, "Canadians enjoy one of the lowest-cost 'food baskets' in the world, spending only about $0.10 of every dollar on food," reminding the reader that low food prices are dependent on maintaining current industrial-scale production methods.

However, as Albert Howard noted long ago about industrial agriculture, "The food was cheap, the product was cheap because the fertility of the land was neglected." It is these connections that reinforce Postuma's and others' concern with the tension between what humans want and what the land will provide.

"You cannot take the economy of nature," says Postuma, "And supplant it with the nature of humans and come out ahead."

The tour wrapped up in Posthuma's home. Attendees ate lunch in her living room and talked more about observing what goes on in our surroundings. Posthuma began a discussion on the way animals transform what they eat and how the manure they produce enriches soil.

A chicken, for example, is able to accomplish the impressive task of digesting rocks with its gizzard. The friction involved in the process creates energy, and that energy goes back to the soil, depositing calcium and other minerals. Cows, meanwhile, which are micro-accelerators of digestion, impart high levels of bacteria. Every animal, when closely observed, makes its own soil-enriching recipe.

As a farmer, Posthuma has been called upon to impart her knowledge and observational expertise to others through presentations and on-farm tours like this one, but she is, as she puts it, "first and foremost a farmer, tending farm." She is a vendor at the Kingston Public Market, and runs two CSA programs, one in Kingston and the other serving the Perth area.

As a vendor, she is not keen to proselytize on the merits of her practices and the quality of her products. "I send out information with every single vegetable I sell, in the vegetable itself," she says. If her efforts toward creating good soil really are making for better food, then, it seems, the food should speak for itself.

Jonathan Davies is a farmer himself, and operates Long Road Eco Farm near Harrowsmith with his partner X.B. Shen. Jonathan is contributing a series of articles called Frontenac Farming Life, which profiles the lives of local farmers who are trying to make a living through farming, navigating struggle and hope. If you would like to have your story considered, please contact Jonathan at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

“Litsie's” Susan Billinghurst sews her way home

Susan Billinghurst, owner of Litsie, a home-based eco-bag business, is a self-confessed “fabric junky” who has been sewing since she was a youngster.

“I remember making clothes for my Barbie dolls when I was a kid and later making a lot of my own clothes as a teenager” she said when I interviewed her at her home in Perth Road last week.

Serious sewing stopped for her decades ago as she raised her three sons and worked as a consumer and family studies teacher. Later she worked as the cooking school coordinator at the Midland Avenue Loblaws in Kingston.

Billinghurst returned to sewing full time two years ago after leaving her Loblaws job due to health reasons. She started up her business designing and creating a line of eco-friendly safe, re-useable snack, lunch and wet bags. Since that time her business has taken off.

The idea for the business came about after she visited her daughter-in-law, a new mom who was using cloth diapers at the time and who longed for a re-useable bag for the diapers. “I made my first 'Litsie' bag then and was encouraged by my family to keep pursuing the business idea," she said.

The name of the business came from her granddaughter Sophia, a toddler who was unable at that age to pronounce her name and called herself Litsie. Susan decided on that as the name for her business. “It could have been Sue Sews or Sue's Sacks but Litsie seemed unique; I liked it and it seemed the perfect fit”.

Her daughter-in-law also designed the Litsie logo, which includes a humming bird and Susan said is also the perfect fit.

Sue's bags come in various sizes. She uses designer fabrics in 100% cotton or organic cotton, which come in a wide range of colorful prints that are perfectly matched to a youngster's aesthetic. Her snack bags are food safe, and their interior linings are made from Procare, which is lead, BPA and phthalate-free and meet the current FDA and CPSIA requirements. Her wet bags are waterproof and lined with PUL, a polyurethane laminate perfect for storing wet swimsuits, gym clothes and cloth diapers. Their large tab zippers allow for easy opening and closing. All Litsie bags are hand sewn by Susan herself. They boast what seems to be an endless number of colourful, elegant and playful patterns that include lady bugs, elephants, birds, helicopters, alligators and more. They are sold separately as well as in sets.

Susan is a big fan of the designers Charlie Harper and Amy Butler, as well as Parson Gray and Michael Miller, the latter of whom design with older buyers in mind. A grant that Susan recently acquired through the Frontenac Community Futures Development Corporation in Harrowsmith allowed her to purchase a brand new Bernina Quilting Edition sewing machine, which has enabled her to add baby quilts and quilted Christmas stockings to her inventory.

A year ago and with the help of her son, Susan opened up Litsie's online Etsy store and also launched her own website where she sells her bags and other products. She also sells at a number of local craft shows and her creations are also available locally at Nicole's Gifts in Verona and Go Green Baby in Kingston.

Like most artisans, one of the challenges of running a successful business for Susan is finding enough time to actually sit down and sew. Working from home does make things easier but still she said, “Finding the time to sew is a constant challenge. At one show I sold out on the Saturday and had to rush home and sew pretty much all night long to have enough inventory for the next day.”

Some of the things she enjoys most about owning and operating her own business are shopping for fabrics and meeting her customers and other artisans both on line and in person. Her products range in price from $8 to $150. To see more of Susan's Litsie creations visit her on Etsy or at www.litsie.ca

Sonset Farm: Self-Sustaining in Local Food Movement

As I drove up Sonset Farm's laneway, I noticed an odd structure sitting near one of their barns. There were stacks of straw bales forming four low-rising walls, and a wooden frame supporting a flat, plastic covering. While I could not see through the opaque film, I imagined greens flourishing in spite of the slush and snow that surrounded them.

My guess was right: farm owner Andrea Cumpson said they were growing spinach and arugula in the warmth of aged compost.

This is not an ordinary farm and Andrea and Orrie Cumpson are not ordinary farmers. While Sonset is a typical dairy farm at its core, over the years it has taken on layers, which have allowed it to be more self-sustaining and, ultimately, more resilient.

While it is common for farmers to buy inputs year after year from suppliers and then ship their products off, essentially leaving a clean slate for the next year, Sonset operates with principles that create loops rather than end points. In a nutshell, crops are grown to sustain animals, and animals, in turn, provide fertility to crops.

This is central to organic agriculture, one of several frameworks that inform how the farm functions.

Cumpson joined her husband, Orrie, 31 years ago on the land he then owned with his mother near Inverary and there sought to work towards organic practices at a time when few resources were available to help farms transition. When a course on ecological agriculture did emerge in the early 1990s, the pair enrolled and it gave them the confidence to begin.

"Orrie could see that the land was improving. It was plowing up so much more beautifully and the tilth was better," she says.

They had the land itself certified as organic in 1996, motivated in large part by their plans to market their spelt crop. Spelt has been more than an isolated addition to their farm's output. It provides much of the nourishment for their pigs and chickens, which they market from their farm gate, as well as providing bedding for cattle, which in turn adds carbon to compost.

The flour that the Cumpsons mill on the farm is another important addition to their overall income. "With the uncertainty of supply management, it's not putting all of our eggs in one basket," she says.

Supply management, a long-standing marketing system in Canada that requires that dairy farmers own quota in order to produce commercially, is another framework within which the farm operates. While supply management provides security of income for dairy farmers, it has attracted widespread criticism for inhibiting competition - controlling the amounts produced domestically and limiting imports with high tariffs. With a couple of trade agreements likely to take effect in the coming years - namely the Canada-Europe Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), neither of which has yet been ratified - farmers are anticipating changes in regulation and competition.

It is possible that supply management would eventually be repealed. Cumpson notes, "I've heard stories of people, before supply management, being sent back when they brought their milk to the local dairy."

The concern is that the downsides of pre-supply-managed farming, such as flooded markets and prices that don't account for the cost of production, could resurface, along with fierce competitions from countries like the U.S, New Zealand, and EU countries, where dairy farmers are subsidized by their governments.

This brings us to another of Sonset’s frameworks: Local Food.

One of the main challenges with trade agreements is how local and national governments balance honouring trade policy with citizens' social, environmental, and economic interests.

Cumpson, a former president of the local National Farmers Union (NFU), is concerned about the scope and lack of transparency of CETA.

"It's so comprehensive and could be detrimental to what a lot of farmers are doing. It's very secretive and there are suggestions that the wording is not in favour of farmers in general," she explains.

The NFU released a report in December 2014 outlining its views on CETA. It states, “From the farmer’s point of view, export market growth has not delivered promised prosperity,” noting that, over the past four decades, as agri-food exports have risen roughly twenty-fold, half of Canada’s farms have folded.

This reality has prompted some farms to go in the opposite direction - to a local focus. Cumpson is not only among the vanguards of the local organic community, she was co-chair of the Feast of Fields committee, which organized events to promote local food starting in 2004. Sonset has become one of the best-established direct-to-consumer farm operations in the region.

Local food remains a niche market, but while government policy has not been supportive of small, community-focused farms, a segment of the consumer population has grown wary of the food industry’s practices, seeking direct relationships with farmers in order to have more knowledge about how their food is produced. Cumpson sees this continuing to grow. “I feel strongly that we're just at the beginning," she affirms.

Meanwhile, the greens that were growing unseen when I drove in will serve as early vegetables in a spring that is about to begin, and with spring comes the green blades of spelt. There is a lively spirit to the farm, in spite of the weather, as it gears up for another season.

Jonathan Davies is a farmer himself, and operates Long Road Eco Farm near Harrowsmith with his partner X.B. Shen. Jonathan is contributing a series of articles called Frontenac Farming Life, which profiles the lives of local farmers who are trying to make a living through farming, navigating struggle and hope. If you would like to have your story considered, please contact Jonathan at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Marcel Giroux: The schools, the arena, the library and the church

Marcel Giroux has been a busy guy since he came to Sharbot Lake High School to teach French and Gym in 1956.

The school he came to was eight years old and it was already showing signs of being too small for the demands of the local community. A few years later, with the baby boomers hitting high school, the school was expanded during a two-year period in which Marcel served as the interim principal.

“The high schools were under the supervision of Frontenac County at that time and the public schools were under the townships. The problem in the high schools was overcrowding. When Sharbot Lake High School was expanded in 1962 it was built on the premise that it would be 100 students in grade 9; 70 in grade 10; 40 in grade 11; 30 in grade 12; and 20 in grade 13,” he said.

Most jobs only required a grade 10 education at that time, but that changed to grade 12 just as the baby boomers were coming through.

“The school was built for 240 students and 380 students showed up in September. We had that problem for years.”

In the late 1960s the push was on to close one room schools and establish larger public schools. Marcel, who was the head guidance counselor at SLHS by that time, a position he held until his retirement in 1988, visited those schools every year to talk to the grade 8 students who were going to come to SLHS the next year. He supported closing the one room schools and expanding Hinchinbrooke, Sharbot Lake, and Clarendon Central Public Schools, and building Land O'Lakes Public School.

“People have a romantic view of one-room schools, but the reality was that of the 14 that were in our townships, one or two were good, most of them were pretty poor, and a couple of them were horrendous. The good ones had established teachers and financial support from the township and community. But that was rare. I remember visiting a school that was being taught by a young girl who had just graduated from high school herself. She was taking chalk out of her purse in the morning because she had to supply it herself. That's the kind of thing that went on.”

In 1969 the Frontenac School Board was established. It included two rural high schools, Sharbot Lake and Sydenham; Lasalle High School in Pittsburgh Township and Frontenac High School in Frontenac Township. The Kingston and Frontenac Board merged sometime later. Eventually Lennox and Addington schools were added and the Limestone Board was established.

Marcel Giroux was elected to municipal council in Oso Township in the fall of 1972, and he had an ulterior motive for seeking office. Within six months of his election he was holding meetings with representatives from three neighboring townships to talk about building an arena, a project he had wanted to make happen for a long time.

“We realised quite quickly that between the four of us we were only big enough to build half an arena. The people in Portland Township were also thinking about an arena and they concluded they were only big enough to build half an arena. So we all got together.

“Portland came up with ten acres of land bordering the boundary road with Hinchinbrooke and we developed a plan and eventually got it built. I remember that since it was built closer to the south than the north and people from Kennebec and Oso had to drive further, it was agreed that Portland would pay 52% of the costs and the other four townships would pay 48% of the costs.”

One of the reasons for the long-term viability of the arena, in Marcel's view, was staffing.

“Jim Stinson was the first manager and he ran that place very well for 40 years. That's probably why it has been so successful.

When Marcel retired from teaching on a wintry Friday in 1988, he took it easy for a day, and then on the Sunday formed a committee to start working on building a new Catholic Church in Sharbot Lake. The congregation had outgrown the 45 seat, unheated church on Road 38 and Elizabeth Street by the mid '60s but for a variety of reasons no new church had been built.

“We had 80 people coming to mass in the winter and 300 in the summer. We said mass in the parking lot of the beer store one Sunday, in the bar at the hotel, in the township hall, until we eventually started holding mass in the high school for 15 years, but we needed a church of our own."

The property where the church is now located had been purchased for $2,500 in 1962, but over 25 years had passed and the congregation had $22,000 in their building fund.

In 1988, freshly retired, Marcel was in a position to jump in.

“The reason it happened then and not before was that Father Brennan, who was new and enthusiastic, had just come to our congregation, and there was also a new bishop in place. Suddenly the things that were in the way disappeared. A two-year fundraising campaign raised over $430,000 and the church took back a mortgage for $169,000 and a new church was completed in 1992.

One of the best fundraising activities was spearheaded by Doris Onfrachuk. A half-finished waterfront cottage was purchased for $60,000 and was then finished using volunteer labour and donated materials. $100 raffle tickets were sold and $132,000 was raised.

In the late 1960s the push was on to establish a Frontenac County Library. In order to make that happen, according to Ontario regulations at the time, the majority of the townships in the county, representing over 60% of the population, needed to establish branches. Pittsburgh and Frontenac townships already had branches in place, and they represented 70% of the population. What was needed, however, was for seven of the other 14 townships to get on board.

Different people took on their own councils to convince them to start up a library branch. Marcel was involved in Oso Township, but as he tells it, the success came from the fact that when a petition asking for a library to be established was brought to Council, the first three names on the petition were those of wives of council members, and the fourth was the name of a woman who was sitting on council herself.

“They had no choice; it was brutal,” Marel recalls. The first branch in Oso was a not much more than a set of shelves in the United Church Hall in Sharbot Lake.

Efforts in other townships were equally efficient and in 1969, 12 of the 16 Frontenac townships joined together to form the Frontenac Public Library.

When municipal amalgamation was about to take place, it became clear that since Pittsburgh and Frontenac townships were joining with Kingston, the Frontenac Public Library was no longer going to be viable.

Marcel was the chair of the Library at the time, and representatives from each branch began meeting in September of 1996 to work out the details of establishing the Kingston Frontenac Public Library.

“We met monthly for a while and then bi-weekly, each time taking on a problem that needed to be solved - and there were many. We had different labour agreements than the city, a different computer system, different procedures. But by the time amalgamation took place, we had all the legal agreements in place, and all the politicians in Kingston and the four new townships had to do was pass bylaws establishing the KFPL - and they did."

While it seems like Marcel Giroux has spent his whole life on public projects, he has also been a husband to Pam since 1968, and is the father of four adult sons.

Reviving regular musical happenings in Harlowe

The community hall in Harlowe has seen an upsurge in activity this past year thanks to the efforts of a few community-minded music enthusiasts. The regular Harlowe Open Mic/Music Jam/Community Potluck, which takes place on the last Saturday of each month, along with the Olde Tyme Fiddlers who play there every third Friday of the month, have been attracting close to 50 guests at each event.

These musical happenings came about thanks to the efforts of members of the Harlowe Rec Club, three of whom I had a chance to meet at the hall on March 28 while the Saturday Open Mic/Music Jam was in full swing.

Marie White said that the new regular events came about after the Saturday evening dances, which had been taking place there for 13 years, since 1997, started to wane. “The dances started to sour”, Marie said, “and because we had to pay the band and pay for the advertising for the dances, well... it just wasn't worth it anymore.”

In an effort to keep some kind of regular musical events happening at the hall, Marie who loves music and just so happens to be the president of the Olde Tyme Fiddlers' Association in Harlowe, with the help of other members of the Rec committee, who include Marie's husband George White, Terry Good, Pat and David Cuddy and Jannette, initiated the Open Mic/Music Jam and Olde Tyme Fiddlers events. These now keep locals and other music lovers from further afield coming back to Harlowe regularly every month. Admission is free and guests are invited to make a donation to the hall to help pay for its upkeep.

Marie pointed out one couple from Enterprise, Al and Louise Taylor who were up dancing. “They come every month all the way from Enterprise and never miss a week”. Music lovers from Harlowe, Hendersen, Enterprise, Northbrook and other hamlets in the area as well as one couple from Ottawa also regularly attend. On the day of my visit the musical entertainers included Jimmy Dix, Mary O'Donnell, Arnold Miller, Kevin O'Donnell, Ray Whitelock, Dave Johnston, Mary Johnston and Doreen Black.

Like most former two room schoolhouses that have been converted into local community centers, the Harlowe hall has become a hub for the local community. Its hard wood floors and ample hall space plus its updated kitchen and washroom facilities make it the perfect place for entertaining large groups.

While I was there, committee members along with volunteers Fay and Ray White were busy setting up the potluck buffet table in an adjacent room with loads of home made desserts and savory dishes. Committee member Terry Good spoke of the history of the hall, which opened in 1948/49 and was run as a school until 1971/72. At that time it was taken over by the Rec hall committee and in 1986 a $60,000 Wintario grant that was matched (and then some) by funds raised by the hall committee group, allowed for some significant renovations These included moving and updating the kitchen and washroom facilities and the addition of a new roof.

While Harlowe over the years has lost its post office and general store (it used to boast three stores), Good said that he is thankful to still have the hall in the community. The Rec hall club members welcome new visitors to come out to Harlowe, where they stress, “All are welcome”. I would bet that the friendly atmosphere, great music and wonderful food will ensure that one visit to Harlowe is not enough.

Alita Battey-Pratt: The story of the village of Latimer and County of 1000 Lakes

Alita Battey-Pratt moved to a historic home on Latimer Road in the 1960s, with her husband, who taught at Queen's University.

They were trying to “get back to the land, to use a phrase from the 60's, grow our own food and all that,” she recalls. After having twin daughters in 1969 and a son several years later, Alita still had had enough time to do some writing, and had taken an interest in the history of the area. She began writing for the Triangle newspaper, which served Storrington, Loughborough and Portland townships at the time.

When the project to create the book, County of 1000 Lakes, started up in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Alita was approached by Ethel Beedell, who came from Battersea, and Jenny Cousineau from Sunbury to work on the Storrington chapter of the book. Alita also ended up writing the Architecture chapter as well. The book is a 550-page people's history of Frontenac County from 1673 - 1973 and was published in 1983,

“I was raising young children and couldn't take a full-time job. It was fun to do and having a group of people who were so committed coming from all over Frontenac County to do it was a great thing. We met probably once a month. Each district doing a chapter would send a representative, and we got to know each other pretty well. Of course there was no Internet or email, so we communicated by phone and even then it was long distance. Unfortunately the manuscripts are only on paper; there is no digital version of anything, and only a fraction of what was written ended up in the book,” she said, when interviewed from her immaculately restored Heritage Home on Latimer Road on a cold, clear, blustery February morning.

All the research for the Storrington chapter gave her an insight into the history, not only of the former village of Latimer, but also of Battersea, Inverary and Sunbury.

One of the many interesting stories of the development of the area in the mid 19th Century was the development of Perth Road and the bridge over Loughborough Lake, which was necessary in order to bring development to Loughborough and Storrington Townships.

Development in the 1830s in the area between Kingston and Loughborough Lake was hampered by a lack of good roads. In fact there are accounts of the requirement that landowners were required to put in a certain amount of time working on public roadways as a form of taxation.

“In 1853, every landowner in Storrington whose assessed property was less than £50 had to perform two days labour on the roads, and this increased to 12 days for wealthier landowners,” said Battey-Pratt in her manuscript.

When it came time to build the major north-south arterial roads, Perth Road through Inverary and Montreal Road through Battersea, the Province of Upper Canada was not interested in paying the entire cost, so “joint committees were formed from county councilors and citizen shareholders."

The Kingston and Storrington and Kingston Mills Road Company was formed in 1852. In 1854, the first 12 mile stretch of road from Kingston to Loughborough Lake was paved, and two toll booths were installed, which brought in £200 in revenue the first year. It cost £7,293 to build the road, including £615 for the bridge over the north shore of Loughborough Lake. By the winter of 1855, a winter road had been built all the way up to Big Rideau Lake, where Perth Road still ends today.

The rights to the road were sold in 1860 to “a triumvirate of three men, A.J. Macdonell, Samuel Smith and Sir J. A. MacDonald”

James Campbell built the first subdivision in what would become Frontenac County in 1855, subdividing his farm to form 2 acre lots along Perth Road in what was subsequently renamed Inverary from the original name, which was Storrington.

The toll on Perth Road remained in place for decades, much to the consternation of many people who made use of it on a regular basis.

Jabez Stoness, who carried the mail for 35 years over the Perth Road, paid $3,000 in tolls over that time.

In one celebrated case, “The wives of men working in the stone quarry north of Inverary refused to pay the toll because 'they were just taking lunches to their husbands'. They raced through the gate, [tollmaster] Charles Gibson went to get the bailiff ... and warrants were made out for the women's arrest. They were summoned to appear in court, held in Osborne's tavern, and the court fined them $16.50,” a hefty fine considering the toll was only 4 cents each way.

Even a toll road can deteriorate, however, and in 1890, Jabez Stoness, no doubt angered by a lifetime of paying fees, refused to pay any further tolls because of the condition of the road. Noting that the county engineer had deemed the road was “dangerous and impeding Her Majesty's travel” Stoness argued that tolls could not be charged until the road was improved and he won the case.

In 1907 the county offered R. H. Fair, who had purchased the road in 1899, $3,000 for the road. An arbitration board set the price at $7,000 and in June of 1907 the purchase was completed. The tolls were removed from Perth Road once and for all, and a steel bridge was constructed over Loughborough Lake, putting an end to decades of difficult crossings over rickety bridges (and ferries when the bridges would collapse every 10 years or so)

One of Alita's interests during the writing of the book was the history of Latimer and the history of her own property, which was originally granted in 1799.

During the research phase for County of 1000 Lakes, a neighbour who was living on the property that at one time had been John Woolf's store, found a sack full of papers which, when inspected, yielded a very clear picture of how the store and the Village of Latimer functioned in the mid 19th Century. At one time Latimer, which was the first settlement north of Kingston in what would become Storrington, had a post office, two cheese factories (including one that was turned into a fire station in the 1970s) a store and other amenities.

John Woolf came to Latimer from Thorold in 1820 or '21, settled and opened a black smith shop, which became a trading post.

Alita is still excited by what those old documents said about life in Latimer almost 200 years ago.

“What I found was that he kept scrupulous records of everybody who came and went from his trading post, because people didn't have cash. If you came in with homespun - the Campbell ladies made a lot of homespun, that has been documented - they would trade that for wheat or flour or scantling [small timbers].

“So you had a document that ran for 50 years, of everything that went on in the community, every family, every trade, recorded in pounds, shilling and pence, until it became dollars and cents after 1850.”

The documents also tell when houses were built and who built them

“Captain Everett, who was a wealthy man and an owner of the toll road, would buy flooring for a full house in one go, and you would get to know when he took on construction projects.

The Ansley family who lived on the farm where Alita lives, were in the lumber business, and most of their trading was done in terms of flooring, scantling and cedar shingles and they would trade for ground flour and ground peas, etc.

Her research also revealed details about the history of her own house and the families that owned and operated it and the surrounding 200 acres of farmland.

“It was built by Amos Ansley, who was a United Empire Loyalist and a well known master builder. It became interesting to me partly because when my husband and I purchased the house it was in a derelict state and we spent years restoring it so we learned a lot about how it was built in the process. But I also happen to be from a Loyalist family myself, and it occurs to me that a master builder such as Ansley would either have crossed paths with my family or at least they would have known about him.”

Amos Ansley Jr. ended up owning a mill in what would eventually become the Village of Battersea.

Ansley sold the mill in 1830 to another Loyalist who moved into the area, Henry Vanluven. Vanluven and his sons became an economic force in what became know as Vanluven's Mills until the name was changed to Battersea in 1857. He was also the first reeve of Storrington Township when it was incorporated in 1850.

“Battersea had a larger population in 1850 than it does now,” said Alita, “and it had a gristmill [which burned down] a number of sawmills in and around the village and a large tannery. It was a thriving industrial centre in its day.”

Tiffany Gift Shop to close in Harrowsmith

As she approaches her 70th birthday, Ann Elvins, who has been the owner of the Tiffany Gift Shop in Harrowsmith for 16 years, says “It's time to dance”.

There never has been a problem with the store, she said. It has been well supported by the community since she took it over.

“I enlarged the store quite a bit. It was a two room store when I bought it and I added another room and a garage and brought in new products, but it kept the same feel as it had when I bought it, which was what I wanted to do,” she said.

She has also been able to support a number of charities with the store, including the African Grandmothers, for whom she has hosted an annual plant sale on the front lawn; the Women for Afghanistan; the Cattail Festival; Harrowsmith Public School and others.

But now it is time to wrap things up and retire, and all this month she's been selling off her stock in advance of a final sale on Saturday, where everything that is left will go for 50% off.

“It's bittersweet because the shop has been a great joy to me, but some of those one-day buying trips to Toronto and other parts of running an ongoing business are no longer things I want to deal with,” she said.

Ann Elvins is not planning to move from her house, which is attached to the store. She will be approaching the township for a permit to convert the store into a senior's apartment and will be able to enjoy more of the activities in the local community now that she will have more free time.

“I'm not going anywhere. If you see me on the lawn or in the garden, honk and I'll wave,” she said.